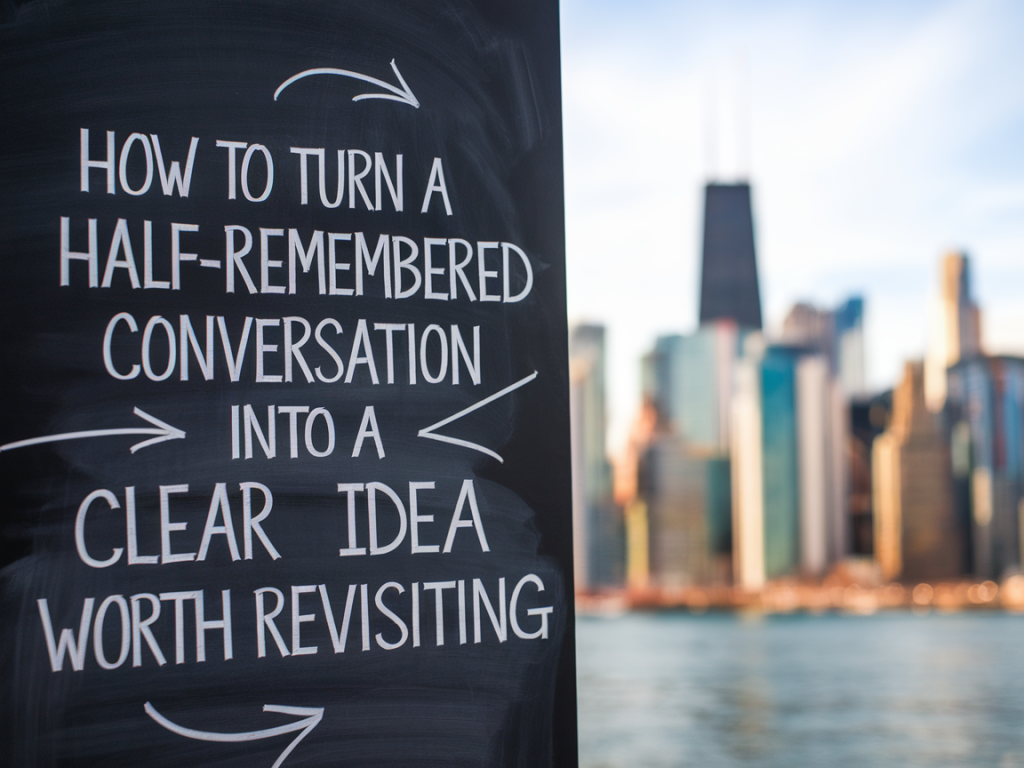

I was walking home one evening when a stray line from a conversation I’d overheard lit up a corner of my mind: “We forget not because memory fails, but because we never wrote the thought a second time.” The line was half-remembered, italicized by my own imagination, and stubborn enough to hang around the way a song does when you can’t quite find the chorus. That stray line turned into a small project: could I capture that fuzz of memory and turn it into something clear enough to revisit and work with?

If you’ve ever left a coffee shop with a nugget of an idea lodged somewhere between “that was interesting” and “I should do something with that,” you know the trouble. The mental equivalent of a sticky note — vivid for a moment, then gone. Over the years, I’ve developed habits and little strategies to rescue those half-remembered conversations from the twilight zone and transform them into ideas that feel worthy of being returned to. Below are the practices I use. They’re simple, domestic, and intentionally forgiving.

Catch the thread quickly

The first rule: don’t expect your memory to be generous. The brain is excellent at compressing experience into impressions; it is poor at preserving the punctuation. When something sticks — a line, a rhythm, a metaphor — I try to capture it within the hour.

That may mean typing into my phone notes app (I favor a plain, frictionless app like Apple Notes or Google Keep) or recording a 20-second voice memo. I don’t judge the form. I write what I remember and what I think it might mean. If I can, I jot down the context: where I was, the voice, any image that accompanied the line. Context is often the key that unlocks the thought later.

Why immediate capture works: writing or recording reduces cognitive load. It shifts the burden of remembering from your fragile short-term store to an external system that you can return to deliberately.

Turn fuzz into a question

Once the initial fragment is safe, I translate it into a question. The question doesn’t have to be analytic or lofty; it just needs to point. From the stray line above I might form: “Why do some conversational lines feel like ideas?” or “Is forgetting a failure or a filter?”

Questions are magical because they provide direction. They don’t demand immediate answers; they open a corridor. When I return to the note later, the question is a gentle provocation that tells me what to look for.

Make a tiny sketch

After a day or two, I revisit the captured fragment and make a small sketching session — rarely longer than fifteen minutes. I set a low bar: no careful prose, no hooks, just associative movement. I list what the line connects to in my life, in other books I’ve read, in films I’ve seen, or in news items. I try to find one concrete image to anchor the thought.

- Who said something similar?

- What emotion did it trigger?

- What scene does it bring back?

These tiny sketches often reveal whether the fragment is genuinely interesting or simply pleasant background noise. Even if the idea is small, the sketch gives it a topology — peaks, valleys, and places you might walk through.

Test it aloud

I treat ideas like clothes: I try them on out loud. I’ll say the question to a friend, or post a sentence on social media, or read it aloud to myself. Speaking an idea changes its shape. You hear the clauses that don’t sit right, the metaphors that feel forced, and the intuitions that actually hold together when they’re voiced.

There’s something about the conversational register that restores the origin of the fragment — it’s often the social cadence that made it appealing in the first place. When an idea survives being told once or twice, it signals it might be worth reworking into something longer.

Give it a versioning system

One practical trick I learned from software friends: versioning. I treat each return to a half-remembered thought as a new version. Version 0.1 might be the voice memo. Version 0.2 is the sketch. Version 1.0 is a fully formed short essay. This framing removes the pressure of instant perfection and normalizes revisiting and revising.

On my blog, I’ll sometimes republish an idea in a new form — remixed, extended, or trimmed — and mark it as a revisit. The meta-note that this is a work in progress invites readers into the process, and it’s honest. Ideas are rarely monoliths; they’re iterations.

Collect sensory anchors

Conversations are as much sensory as they are semantic. The timbre of a voice, the clink of teaspoons, the smell of rain on pavement: these are the scaffolding that can hold a thought steady. When I capture a fragment, I also jot a sensory detail or two. Later, these tiny anchors often become the entry point for a fuller piece of writing.

For example, a half-remembered line about forgetting became a piece anchored by a memory of a train station announcement and the staccato hiss of brakes. That tactile detail made the abstract thought feel concrete and revisitable.

Allow a companion reading list

Sometimes a fragment invites research. I keep a running “companion” list for ideas: a short list of books, essays, or films that might deepen the thought. It’s rarely a formal literature review — more like a curiosity list: a paragraph from Virginia Woolf, an interview with an architect, a podcast episode about memory.

Those companions matter because they give the idea a dialectical partner. Conversation begets conversation, and the half-remembered line often grows stronger when placed beside another mind’s work.

Let it sit, then return

Finally, I try to give the idea time. Not everything should be resolved quickly. Some half-remembered conversations are seeds that need seasons. I’ll drop the file into a folder labeled “Ideas / Slow” and forget it for a month. When I open it again, my relationship to it will have changed. Sometimes the idea has withered; sometimes it has rooted in new, surprising ways.

Trusting the pause is an act of kindness to thought. It stops you from flattening every mental twitch into content. It gives the stray line the dignity of slow attention.

If you’re wondering where to start: begin with a single sentence you overheard today. Save it. Ask one simple question about it. Spend ten minutes sketching. Then wait and see. You might be surprised how many half-remembered conversations are really invitations to think more carefully, to write more kindly, and to return, again and again, to the small things that shape how we see the world.